Large-scale DNA study maps 37,000 years of disease history

A new study maps infectious diseases across millennia and offers new insight into how human-animal interactions permanently transformed our health landscape.

A research team led by Eske Willerslev, professor at the University of Copenhagen and the University of Cambridge, has recovered ancient DNA from 214 known human pathogens in prehistoric humans from Eurasia.

The study shows, among other things, that the earliest known evidence of zoonotic diseases – illnesses transmitted from animals to humans, like COVID in recent times – dates back to around 6,500 years ago, with such diseases becoming more widespread approximately 5,000 years ago. It is the largest study to date on the history of infectious diseases and has just been published in the scientific journal Nature.

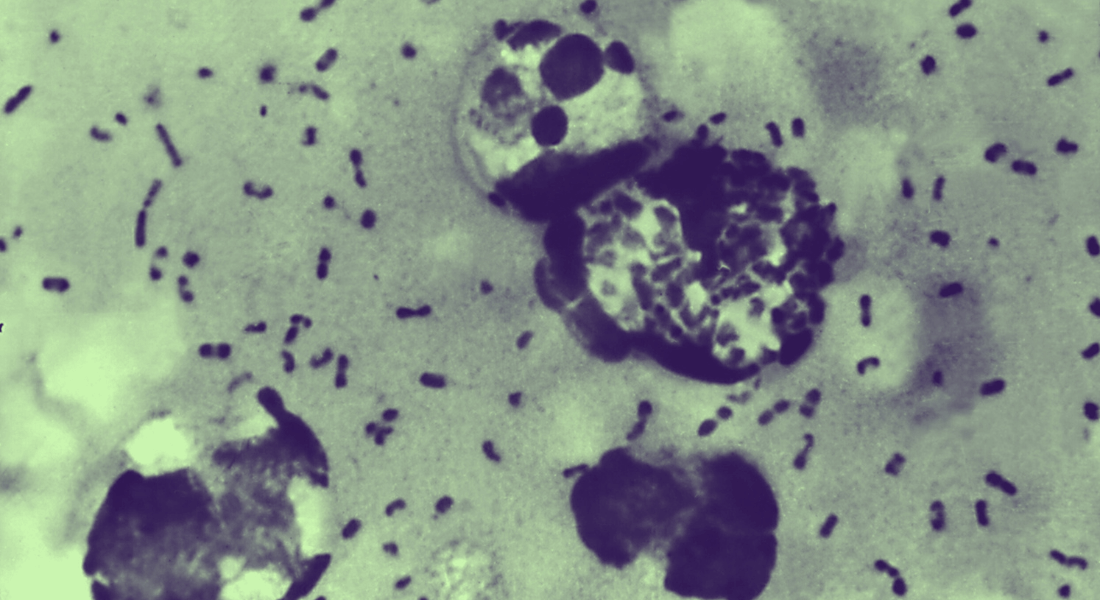

The researchers analyzed DNA from over 1,300 prehistoric individuals, some up to 37,000 years old. The ancient bones and teeth have provided a unique insight into the development of diseases caused by bacteria, viruses, and parasites.

The results suggest that humans’ close cohabitation with domesticated animals – and large-scale migrations of pastoralist from the Pontic Steppe – played a decisive role in the spread of these diseases.

“We’ve long suspected that the transition to farming and animal husbandry opened the door to a new era of disease – now DNA shows us that it happened at least 6,500 years ago,” says Professor Eske Willerslev. “These infections didn’t just cause illness – they may have contributed to population collapse, migration, and genetic adaptation.”

Could have implications for future vaccines

The findings could be significant for the development of vaccines and for understanding how diseases arise and mutate over time.

“If we understand what happened in the past, it can help us prepare for the future, where many of the newly emerging infectious diseases are predicted to originate from animals,” says Associate Professor Martin Sikora, the study’s first author.

“Mutations that were successful in the past are likely to reappear. This knowledge is important for future vaccines, as it allows us to test whether current vaccines provide sufficient coverage or whether new ones need to be developed due to mutations,” adds Eske Willerslev.

The study was made possible by funding from the Lundbeck Foundation.

Read the study “The spatiotemporal distribution of human pathogens in ancient Eurasia”.

Contact

Professor Eske Willerslev

Globe Institute

Email: ewillerslev@sund.ku.dk

M: +45 28 75 13 09

Associate Professor Martin Sikora

Globe Institute

Email: martin.sikora@sund.ku.dk

M: +45 93 56 54 03

Communications officer Henriette Meier-Jensen

Globe Institute

Email: henriette.meier-jensen@sund.ku.dk

M: +45 22 18 02 28