Researchers: "We should not think of the antibiotic resistance crisis as something in the future. It is already here"

Antibiotic resistance is a serious health crisis that is getting far too little attention. In 2019, five million deaths worldwide were associated with antibiotic resistance. The solution is both simple and surprisingly difficult to implement, says two experts in a call for action on a crisis in full bloom.

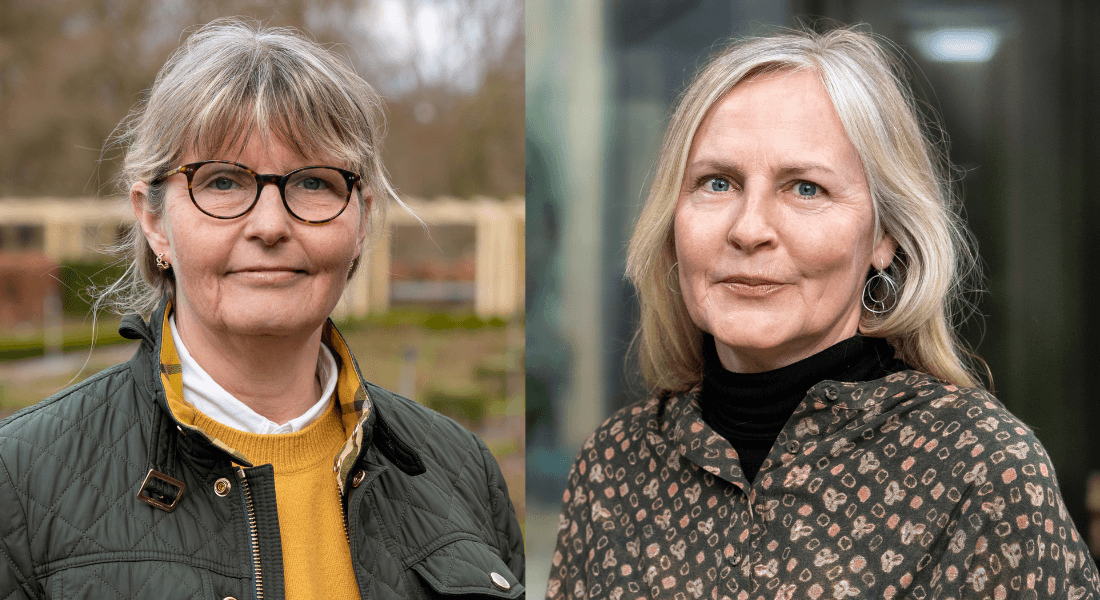

Dorte Frees and Hanne Ingmer love bacteria.

They find these tiny single-cell organisms extremely fascinating. That is why they spend most of their waking hours trying to understand bacteria. What do they consist of? How do they work? And most importantly, what can kill them?

Because while Dorte Frees and Hanne Ingmer are enthusiastic about bacteria’s high level of “intelligence”, they are less excited about their increasing ability to resist antibiotics – a “scary” development, says Associate Professor Dorte Frees, who has spent 20 years researching antibiotic resistance.

It is pure Darwinism – the weak bacteria die and the ones who develop resistance survive. Therefore, the more antibiotics we use, the more resistant bacteria we get

“In 2019, five million deaths worldwide were associated with resistant bacteria. So don’t think the antibiotic resistance crisis is coming – it is already here. It is clear when you look at countries like the US, India or China,” she says.

Professor Hanne Ingmer, who also has 20 years’ experience in this area, nods and adds that the situation is less serious in Denmark, which is not as reassuring as it sounds, though:

“Overall, the situation in Denmark is fine if we only focus on the narrow local level. But of course, that would be naïve of us. Because Danes love to travel, and we import lots of different foods. Some resistant bacteria are found in ballast water from large ships which is discharged into the sea all over the world, including Danish waters,” says Hanne Ingmer.

The more antibiotics, the more resistant bacteria

In Denmark, the majority of resistant bacteria are found in hospitals, Dorte Frees says and explains:

“It is because hospitals have a high concentration of antibiotics, and the more antibiotics you use, the more bacteria and the more resistant bacteria you get.”

This is how antibiotic resistance works: When bacteria like Streptococcus pneumonia which causes pneumonia are exposed to antibiotics, the bacteria will in time develop defence mechanisms – resistance.

“It is pure Darwinism – the weak bacteria die and the ones who develop resistance survive. Therefore, the more antibiotics we use, the more resistant bacteria we get,” she stresses.

People in poor health are more sensitive than others to resistant bacteria, which can lead to severe illness or death.

A slow-building catastrophe

Researchers have known for many years that bacteria can develop resistance to antibiotics. Soon after a Scottish microbiologist discovered the first and perhaps most well-known type of antibiotic, penicillin, back in 1928, it became clear that some bacteria become resistant.

“Penicillin was a miracle cure that made it possible to defeat some of the deadliest bacterial infections. E.g., before penicillin and other types of antibiotics were introduced, the risk of dying from pneumonia was 50 per cent,” says Dorte Frees.

Moreover, antibiotics have virtually no harmful side effects, and they have made it possible to perform a number of procedures, e.g. chemotherapy and transplantations, previously associated with a considerable risk of deadly infections. Therefore, antibiotics have been considered a harmless “wonderdrug” often used “for safety’s sake”.

“Many countries – including India, China and Eastern Europe – allow over-the-counter sale of antibiotics. Unlike Denmark, you don’t need a prescription to buy antibiotics,” says Hanne Ingmer.

Is the consumption of antibiotics in these countries higher than in the rest of the world?

“Yes, both the amount of antibiotics used and the level of resistance is higher in these countries,” says Hanne Ingmer and adds:

“While India has seen a great increase in the use of antibiotics, its rivers have been polluted with resistant bacteria from factories producing antibiotics for i.a. the Western world. It is really scary.”

Farmers are left in the lurch

The only fundamental solution to antibiotic resistance is simple: Use less and only when it cannot be avoided.

“Because there is a clear connection between antibiotic consumption and resistance, we clearly have to be far more careful only to use antibiotics when there is no avoiding it. So ‘for safety’s sake’ does not apply here. Using antibiotics is not without consequences,” says Dorte Frees and adds:

“And that is why I believe the current level of antibiotic use in farming is absolutely crazy. What is there to gain? Cheap meat. But in the long run there is a lot more to lose, because multi-resistant bacteria can pass from animals to humans.”

Overall, the situation in Denmark is fine if we only focus on the narrow local level. But of course, that would be naïve of us.

Hanne Ingmer interrupts:

“But it is tricky, because if Danish farmers have to compete with Chinese and Indian farmers, who have unlimited access to antibiotics, they will lose.”

Dorte Frees nods and adds:

“Exactly. We are leaving farmers in the lurch here. Policymakers should give them a hand by supporting safe meat production which limited use of antibiotics.”

An arms race against bacteria

We need to radically reduce the amount of antibiotics used by humans and animals. At the same time, researchers all over the world are working on alternative methods for fighting dangerous bacteria, including Dorte Frees and Hanne Ingmer.

“We have received EU funding for research into resistant bacteria and for training of a new generation of European researchers. We will be studying the cell wall of bacteria to see if it offers a way to render the bacteria harmless,” says Hanne Ingmer.

Other researchers are studying bacteriophages, which are viruses that only affect bacterial cells. Existing research suggests that bacteriophages are more or less harmless to humans.

“They are able to target bacteria without harming the human cells, and to some extent they are indifferent to resistance. The problem is that bacteria can become resistant to bacteriophages. It is a race,” says Hanne Ingmer.

Dorte Frees adds:

“Yes. It is an arms race. Even if we develop a new miracle cure, we have to reduce our use of antibiotics.”

Contact

Associate Professor Dorte Frees

df@sund.ku.dk

+45 35 33 27 19

Professor Hanne Ingmer

hi@sund.ku.dk

+45 22 15 95 18

Journalist and press consultant Liva Polack

liva.polack@sund.ku.dk

+45 35 32 54 64