You can feel this acid when you work out. Now it may increase knowledge of cancer medicine

New research shows that specific enzymes can remove lactic acid marks. This finding may increase our understanding of cancer medicine and how physical exercise, among other things, can affect human epigenetics.

When the muscles become acidic after doing too many press-ups, squats or cycling to work, it is because of lactic acid.

Strained muscles produce energy fast, and a by-product of that process is lactic acid. However, lactic acid is also abundant in cancer cells, which invest a lot of energy into dividing and forming tumours.

Now a new study from the University of Copenhagen reveals that specific enzymes can remove lactic acid marks from proteins, and the researchers hope this will increase our understanding of the effect of cancer medicine, among others.

“Of course, the ultimate goal is to develop drugs with as few side effects as possible,” says Professor Christian Adam Olsen from the Department of Drug Design and Pharmacology, who is responsible for the new study. He adds:

“The more knowledge we are able to generate about the enzymes that are able to remove lactic acid marks, the easier it will be to design new drug candidates capable of targeting these specific enzymes. So the discovery may affect the development of new cancer medicine using these enzymes as the target.”

The process that leads to lactic acid both helps the body out in connection with e.g. physical exercise and corrupts it in connection with cancer. Therefore, it is interesting to determine how the level of lactic acid affects the human cells.

Present in the photo are four of the seven researchers from the University of Copenhagen who have contributed to the study. Photo: UCPH

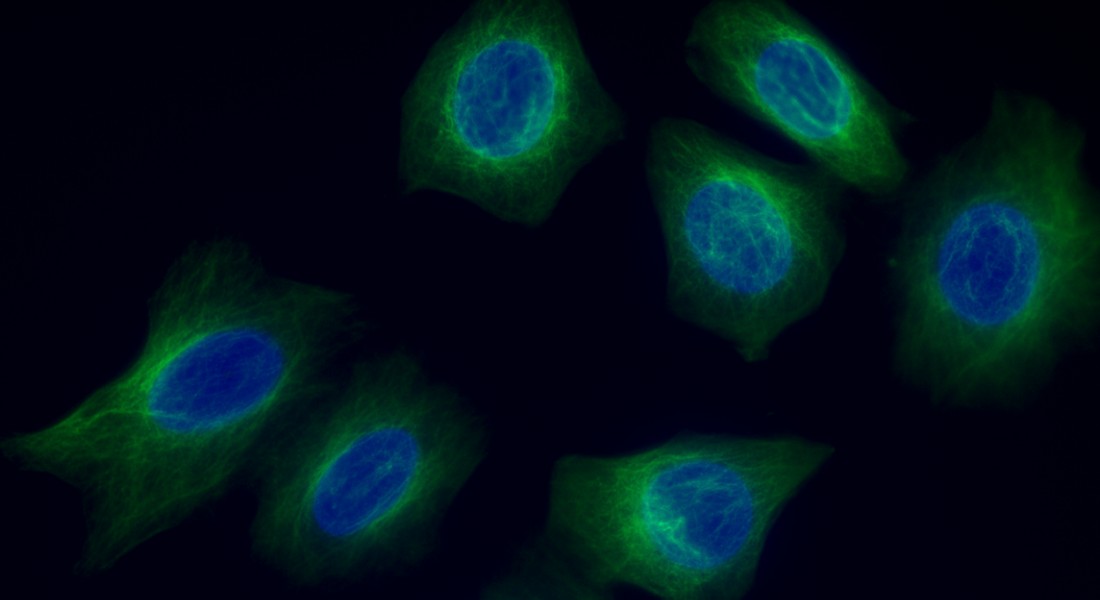

Fluorescent cell parts

As part of the study, Christian Adam Olsen and the rest of the research team – which also includes a team based at the University of Chicago headed by Professor Yingming Zhao – have grown healthy human cells as well as cancer cells in the laboratory.

Several of their experiments involve breaking the cells in order to study the various parts in more detail using specific antibodies. However, they also studied living cells directly using reagents able to make selected cell components fluorescent.

According to the first author of the study, Postdoc at the University of Copenhagen Carlos Moreno-Yruela, this showed that these specific enzymes indeed remove lactic acid marks.

“The level of lactic acid increased significantly when we removed these enzymes. The same happened when we inhibited the enzymes using existing cancer medicine,” says Carlos Moreno-Yruela.

Besides hoping that the results of the new study are able to contribute to the development of new cancer medicine, the researchers believe their discovery increases our understanding of epigenetics.

Because the lactic acid in our cells may end up as epigenetic marks that affect the way genes are read. Unlike genetics – which we inherit from our parents – our epigenetics can change throughout life.

Diet, sleep and physical exercise are some of the factors that can affect our epigenetics, previous research has shown.

“We still do not know whether lactic acid marks are inherited. But if they are, it might be interesting to study the possible effect of e.g., diet, sleep and physical exercise on the epigenetic marks of the next generation. To answer such a question, you might start by studying e.g. mice or other animal models,” Christian Adam Olsen concludes.

Read the entire study, ‘Class I histone deacetylases (HDAC1–3) are histone lysine delactylases’, in Science Advances.

The research conducted at the University of Copenhagen was funded by the Independent Research Fund Denmark and an ERC Consolidator Grant.

Contact

Professor Christian Adam Olsen

22 28 20 06

cao@sund.ku.dk

Press Officer Liva Polack

23 68 03 89

Liva.polack@sund.ku.dk